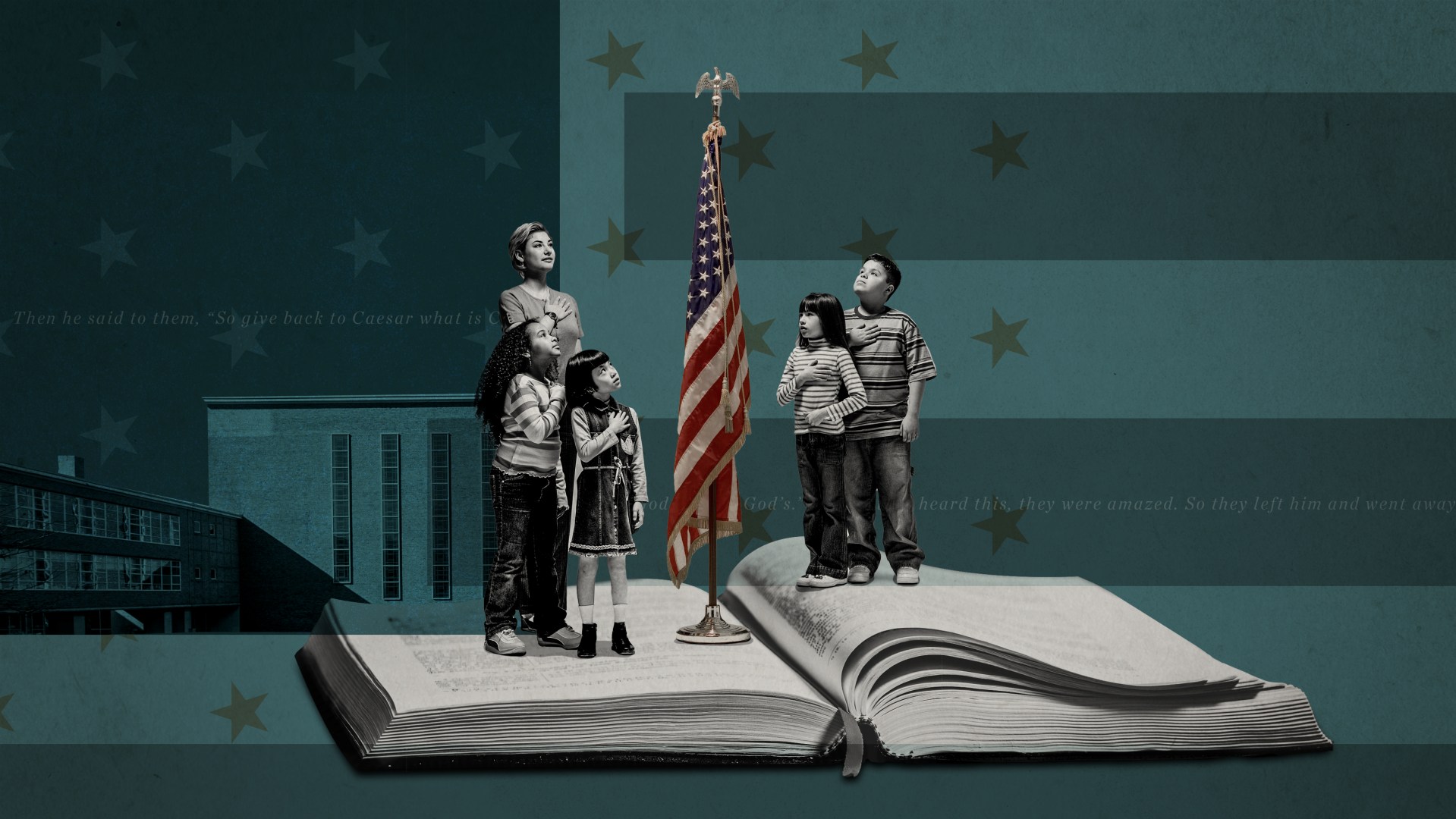

The season of Lent provides a rich time of confession and prayer and is often accompanied by fasting from food or other indulgences. I didn’t grow up observing Lent, but as I’ve learned more about the church calendar, I’ve grown to appreciate the practices that bring meaning and depth to the journey toward Easter.

Lent is modeled after the 40 days Jesus spent fasting in the desert before being tempted by the devil (Matt. 4:2). In actuality, however, Lent lasts longer than 40 days because Sundays are not included. Sunday is always the day of Resurrection, calling for feasting rather than fasting. Sundays during Lent are thus often referred to as “little Easters,” interruptions of sheer joy on the longer and more sober 40-day journey. Little Easters provide small but glorious fueling stations on our way to Resurrection Day.

As Saint Augustine said of these Sundays in Lent, “fasting is set aside and prayers are said standing, as a sign of the Resurrection, which is also why the Alleluia is sung on every Sunday.”

As I have learned about these small, celebratory interludes during the typical pattern of Lent, I’ve wondered if they could be a model for other long-enduring times of sacrifice. Claiming small, joyous moments, even when living in the serious reality of the present, keeps in our minds the whole story of God. Little Easters along the way provide for us strength to press on.

The reality of suffering

Not all who observe Lent break their fast on Sundays. Even small moments of feasting during such a serious season can feel scandalous. Similarly, in other serious times of life, small moments of joy can seem inappropriate. Any celebration risks dismissing the gravity of hardship at hand.

This was the case for a young minister in South Africa in 1985 named Trevor Hudson. South Africa was suffering its long, oppressive history of apartheid, and most believed God did not regard their suffering.

Trevor was relieved to read Jurgen Moltmann’s The Crucified God,which emphasized our communion with God in suffering. Far from abandoning us, God was shown to suffer alongside his people. Hudson began to assert to his congregation that Christ crucified was the foundation for all Christian theology.

The young pastor, realizing the inevitability of hardship, found comfort in God being with us there. What happened in the Crucifixion did make for a robust theology of suffering. However, reducing his theology to Jesus’ death proved insufficient for the whole of human experience.

“Is your God gloomy?”

One of Trevor’s friends in ministry began writing a book, and he invited Trevor to read through the manuscript. His friend, Dallas Willard, author of The Divine Conspiracy, wrote that God “is the most joyous being in the universe.”

Trevor knew Dallas’s words to be honest. When visiting the South Africans, Dallas was joyfully present to everyone he met. But Trevor was nevertheless resistant. How could God be seen as joyful amid such obvious hardship?

Dallas responded by asking, “Trevor, is your God gloomy?” Trevor had been noticeably pessimistic for some time. Honoring the hardship surrounding him had prevented him from looking for resurrection joy. He realized he needed to remember the whole story.

God suffers with us, but God also exudes joy. Trevor reread the Gospels and was struck by Jesus’ delight in shared meals, good wine, and playful children. He embraced moments even in the midst of the hardship of his own life and the serious needs he saw around him. Jesus showed that simple joys can happen even in serious times.

Hard times and the necessity of joy

Knowing his death was imminent, Jesus assured his disciples of their connection, like a vine and branches, and of their eventual reunion. He said, “I have told you this so that my joy may be in you and that your joy may be complete” (John 15:11). They would need deposits of the joy to come, given all that transpired over Good Friday and Saturday. Horror and sorrow, disappointment and doubt disturbed his disciples to the extent that they abandoned him.

Lent invites me to reflect on my own sin. The sign of the cross, ash-traced on my forehead, indicts me every Ash Wednesday and presses upon me the depth of Christ’s sacrifice. But Jesus also shows my heart mercy, as he did his disciples, in tracing reminders of the rest of the story on my heart. I grasp both the grief and the glory.

The little Easters in all of life

As Sundays during Lent override the somberness of the other days, so the joy of my life in Christ removes the sting of death, brokenness, and suffering. I’m tempted to wait until the pandemic subsides before engaging in a moment of celebration. I’ve been storing celebrations in my mind, waiting for lifted restrictions and herd immunity before saying any alleluias. I’m starting to wonder, though, if Jesus’ life frees me to imbibe now from the always-available joy that is already mine in him. As theologian N. T. Wright reminds, as believers, we are “bringing fragments and flashes of new creation to birth in the midst of the still-darkened and sorrowing world.” I want the darkened and sorrowing world around me to see glimpses of that kind of hope.

The opportunities are all around us. What little Easters can we celebrate now? What words could we speak to showcase joy and new birth?

Kathryn Maack is the cofounder of Dwell, a worship and discipleship movement helping men and women fully experience life with God.