In this series

Editor’s note: The 2022 World Watch List has been released, and CT offers results and analysis in 10 languages.

Every day, 8 Christians worldwide are killed because of their faith.

Every week, 182 churches or Christian buildings are attacked.

And every month, 309 Christians are imprisoned unjustly.

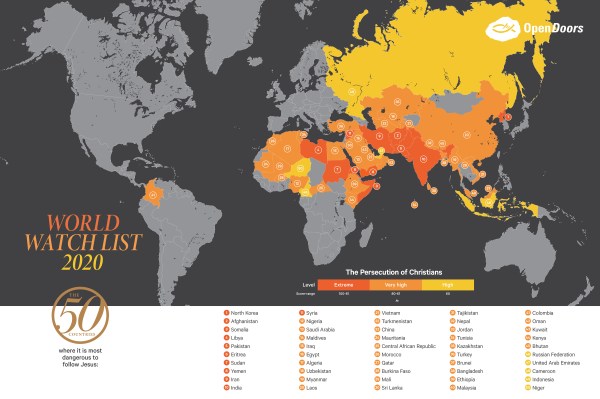

So reports the 2020 World Watch List (WWL), the latest annual accounting from Open Doors of the top 50 countries where Christians are the most persecuted for their faith.

“We cannot let this stand,” said David Curry, president and CEO of Open Doors USA, during the 2020 list’s unveiling in Washington, DC, this morning. “People are speaking out and we have an obligation to hear their cry.”

The listed nations comprise 260 million Christians suffering high to severe levels of persecution, up from 245 million in last year’s list.

Another 50 million could be added from the 23 nations that fall just outside the top 50—such as Mexico, Chad, and the Democratic Republic of the Congo—for a ratio of 1 in 8 Christians worldwide facing persecution.

Last year, 40 nations scored high enough to register “very high” persecution levels. This year, it reached 45.

Open Doors has monitored Christian persecution worldwide since 1992. North Korea has ranked No. 1 since 2002, when the watch list began.

The 2020 version tracks the time period from November 1, 2018 to October 31, 2019, and is compiled from reports by Open Doors workers in more than 60 countries. The list “provides the most comprehensive grassroots data on Christian persecution,” said Curry. “But it is much more than that. It is sounding an alarm.”

Last year, CT noted “Asia Rising” as India entered the top 10 for the first time while China rose from No. 43 to No. 27.

That trend continues, as 2 in 5 Asian Christians now face high levels of persecution, up from 1 in 3 the previous reporting period. China’s crackdown on both state-sanctioned and underground churches and its growing surveillance network added 16 million to Open Doors’s tally of Christians facing persecution.

“The Chinese government is committing unparalleled human rights crimes against Christian citizens and seeking to wipe religious sentiment from its country,” stated Curry in a press release ahead of today’s event. “Yet, as the Chinese Christians who will join me will testify, the persecution Christians face—including extensive surveillance, raids on churches, and imprisonment—have not succeeded in eliminating Christianity.

“Instead, the underground Christian community has banded together and is actively working to call the world’s attention to the plight of the Chinese people. We will join them in that call.”

At the DC rollout, Curry was joined by Chinese pastor Jian Zhu. “The persecution of Christians is the worst I have seen since 1979,” he said. “Christians have a worldwide brotherhood, and the government sees this as a threat.”

“It is time for religious persecution to stop once and for all,” said Robert Destro, Assistant Secretary of State in the US State Department’s Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor, at today’s rollout. “But as we all know, that is a long-term proposition.”

The point of the annual WWL rankings—which have chronicled how North Korea now has competition as persecution only gets worse and worse, is to aim for more effective anger while showing persecuted believers that they are not forgotten.

This year the top 10 is relatively unchanged. After North Korea is Afghanistan (No. 2), followed by Somalia (No. 3), Libya (No. 4), Pakistan (No. 5), Eritrea (No. 6), Sudan (No. 7), Yemen (No. 8), Iran (No. 9), and India (No. 10).

Open Door USA

Open Door USAOpen Doors tracks persecution across six categories—including both social and governmental pressure on individuals, families, and congregations—and has a special focus on women.

But when violence is isolated as a category, the top 10 persecutors shifts dramatically—only Pakistan and India remain.

Five of the most violent countries for Christians are located in the Sahel, a horizontal belt of semi-arid grazing areas and farmland located between the Sahara Desert and the African savannah.

Militant Islamist rebel groups and terrorists have proliferated in the Sahel in recent years. Conflict between Muslim herders and Christian farmers has also resulted in violence. And weakened government structures leave the population vulnerable.

Nigeria, where Africa’s largest Christian population has no cheeks left to turn, ranked No. 12 overall but is second behind only Pakistan in terms of violence, and ranks No. 1 in the number of Christians killed for reasons related to their faith. Open Doors tallied 1,350 Nigerian martyrs in its 2020 list.

The Central African Republic (ranked No. 25 overall) ranks fourth in violence against Christians. Burkina Faso (No. 28) ranks fifth. Cameroon (No. 48, its first time on the list) and Mali (No. 29) join Egypt (No. 16), Colombia (No. 41), and Sri Lanka (No. 30) in rounding out the top 10. (Another Sahel country, Niger (No. 50), rejoined the list for the first time in five years.)

Sri Lanka rose 16 spots from No. 46 last year, primarily due to the Easter suicide bombings which killed over 250 people at Catholic and Protestant churches, and hotels.

But the year’s largest and most dramatic jump was in Burkina Faso, which jumped 33 slots after not even qualifying for the top 50 last year (it would have been No. 61).

Dozens of Burkinabe priests and pastors have been kidnapped or killed. Over 200 churches have been forced to close. The United Nations estimates 500,000 people have been displaced from their homes. The African Center for Strategic Studies calculates that extremist attacks have quadrupled since 2017, and deaths from violence increased 60 percent in 2019. Open Doors counted 50 Christians among that number.

Meanwhile, a transition in Nigeria from village raids to kidnapping by militant Muslim Fulani herdsmen—whose attacks were six times as deadly as Boko Haram’s, according to the International Crisis Group—resulted in an overall decrease in Christians killed in the Sahel, as well as worldwide.

Due to this shift in tactics, worldwide martyrdoms fell to 2,983 in the 2020 report, down from 4,305 the year before. (Open Doors is known for favoring a more conservative estimate than other groups, who often tally martyrdoms at 100,000 a year.)

Abduction of Christians is a new category tracked by Open Doors in this year’s report, with 1,052 tallied worldwide. Nigeria tops the list, with 224.

Nigeria also leads the newly tracked categories of forced marriages (accounting for 130 out of 630 worldwide), attacked Christian homes (1,500 out of 3,315), and looted Christian shops (1,000 out of 1,979).

Other new categories return the focus to Asia.

Of the top 7 nations where Christians are raped or sexually harassed, 4 are recipients of migrant workers in the Arabian Peninsula: Saudi Arabia (No. 13), Qatar (No. 27), Kuwait (No. 43), and the United Arab Emirates (No. 47). Nigeria is eighth. Worldwide there were 8,537 recorded cases, but Open Doors warns this tally is just the tip of the iceberg, as many assaults occur in private and are not reported.

India ranks first in the new category of physical or mental abuse, which includes beatings and death threats. The continuing rise in the subcontinent of a militant Hindu nationalism contributed to 1,445 of the reported 14,645 cases worldwide.

China is the chief violator in Open Doors’s other two previously tracked categories.

Beijing has jailed or detained without charge 1,147 Christians for faith-related reasons, out of a total of 3,711 worldwide. This number rose from 3,150 last year.

But attacks and forced closures of churches have skyrocketed from 1,847 to 9,488, with China accounting for 5,576.

Angola was second with 2,000 and Rwanda was third with 700. (Neither ranks among the top 50 persecution countries; Angola would be No. 68, Rwanda No. 71.)

Open Doors cautioned that in several nations, the above violations are very difficult to document precisely. In these cases, round numbers are presented, always leaning towards conservative estimates.

Its research is certified and audited by the International Institute for Religious Freedom, a World Evangelical Alliance-backed network based in Germany.

In the Middle East, Open Doors noted little change, with 4 of 5 Christians experiencing “high” levels of persecution. The main and continuing trend is the dwindling number of Christians from Syria (No. 11) and Iraq (No. 15).

Syria has lost 75 percent of its Christian population since the outbreak of civil war in 2011, down to 744,000 last year from an estimated 2.2 million. Iraq has lost 87 percent of its Christian population since the Gulf war in 2003, down to 202,000 last year from an estimated 1.5 million.

Open Doors believes it is reasonable to call Christianity the world’s most severely persecuted religion. At the same time, it notes there is no comparable documentation for the world’s Muslim population.

All nations of the world are monitored by its researchers and field staff, but in-depth attention is given to 100 nations and special focus on the 73 which record “high” levels of persecution (scores of more than 40 on Open Doors’s 100-point scale).

The only good news in the 2020 watch list comes from Ethiopia (No. 39), where recent reforms removed 2.5 million from Open Doors’s global total of Christians facing high levels of persecution. Despite increasing sectarian strife as its Nobel Prize-winning evangelical president makes peace and attempts reforms, the Horn of Africa nation declined in rank from No. 28 to No. 39.

Open Doors also noted the positive case of Pakistan’s Asia Bibi. In May 2019, the Christian mother of five was allowed to emigrate to Canada after the Supreme Court of Pakistan overturned her death penalty conviction for blasphemy. She had been in prison for nine years.

“The suffering of persecuted Christians cannot be recorded in statistics,” stated Open Doors. “Millions of people are found behind the numbers. Each one of them has their own story.

“This often includes deep suffering, but also courage and strong faith.”