In this series

“Next to the Word of God, music deserves the highest praise. … But any who remain unaffected [by music] are clodhoppers indeed and are fit to hear only the words of dung-poets and the music of pigs.”

As might be guessed, these are the words of Martin Luther, the reformer who didn’t mince words. But in more ironic words before these, he said this about music:

Looking at music itself, you will find that from the beginning of the world it has been instilled and implanted in all creatures, individually and collectively. … Music is still more wonderful in living things, especially birds, so that David, most musical of all kings, and minstrel of God, in deepest wonder and spiritual exultation praised the astounding art and ease of the song of birds in Psalm 104. … And yet, compared to the human voice, all this hardly deserves the name of music, so abundant and incomprehensible is here the munificence and wisdom of our most gracious Creator.

Luther was a music lover; he played the lute and flute, sang with a light tenor voice, and even put a hand to composing music. He was well acquainted with the music styles of his day, and he used his varied musical talents and interests to reform the religious and liturgical music of the emerging Lutheran church.

We’ve just commemorated the 500th anniversary of Martin Luther’s 95 Theses. The emphasis was understandably on Luther’s theology—salvation by faith alone, the priesthood of all believers, the priority of Scripture, and so forth. Just as important historically are Luther’s contributions to church music. Though there is no mention of music in the 95 Theses, Luther’s influence on church music has been significant. Martin Luther might be considered with justification “the father of Protestant music in Germany.”

Relevant Words

One legacy that can still be felt today is Luther’s belief that there must be a balance between a simple, accessible musical style and the use of the vernacular in the text. As he put it, “Both text and music, accentuation, melody and gait, must come from the true mother tongue and voice.” Indeed, Luther was a skilled composer, but his true legacy lies in the way he incorporated new texts into the early Protestant church that still speak to us today. The most famous remains “A Mighty Fortress Is Our God,” the first verse of which reads,

A mighty fortress is our God,

a bulwark never failing;

our helper he, amid the flood

of mortal ills prevailing.

For still our ancient foe

does seek to work us woe;

his craft and power are great,

and armed with cruel hate,

on earth is not his equal.

(Luther’s original, by the way, read like this:

A firm castle/fortress is our God,

a good defense and weapon,

he helps us free from all distress that now has struck us.

The old evil enemy means it seriously,

great might and much deception are his terrible armament,

on earth is not his equal.)

Luther insisted hymns speak plainly and forthrightly. He was especially concerned that music affect the youth of his day:

I should like young people, who in any case should and must be instructed in music and in other proper arts, to have at their disposal something which will rid their minds of lascivious and sensual songs, and teach them instead something wholesome, and in their way they may become acquitted with goodness in a joyous manner, as befits the young.”

And later, speaking directly to youth, he said,

And you, my young friends, let this noble wholesome and cheerful creation of God be commended to you. By it you may escape shameful desires and bad company. At the same time, you may by this creation accustom yourselves to recognize and praise the Creator. Take special care to shun perverted minds who prostitute this lovely gift of nature and of art with their erotic rantings, and be quite assured that none but the devil goads them on to defy their very nature, which would and should praise God its Maker with this gift.

One can still see today how much of church music continues to be driven by the tastes and preferences of younger believers. But whether he was thinking about believers young or old, Luther’s passion for a clear text was this:

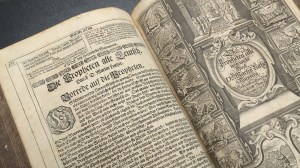

We intend to follow the example of the prophets and the ancient Fathers of the church, and to make a collection of a certain number of psalms for the people, so that the word of God may be kept alive in their hearts by song.

Accessible Music

Still, Luther knew that the power of music went beyond texts. So he also encouraged a new style of congregational participation: the chorale—unison singing, mostly syllabic text setting (meaning single words are not stretched over several different notes), in strophic form (in which all the stanzas are sung to the same music), and a capella, the organ only providing the pitch. Choirs in his churches often sang from within the congregation to provide teaching and support.

In 1524, Luther and Johann Walter published the “first Protestant hymnbook” (even though the term Protestant hadn’t been coined; neither, incidentally, had the term chorale which does not appear until after Luther’s death). Both Luther and Walter wrote distinctive, singable melodies that moved between consecutive notes and didn’t require too great of a vocal range.

Luther freely adapted popular tunes of his day in three ways. First, words were replaced while the music remained. For example, Victimae paschali laudes (“Let Christians offer sacrificial praises”), a Latin Easter sequence, became Christ lag in Todesbanden (“Christ lay in death’s bonds”); this new wording was used by many later German composers including Samuel Scheidt, Andreas Hammerschmidt, and J. S. Bach.

Second, words were replaced and music adapted. For example, Veni redemptor gentium (“Come redeemer of the people”), a Latin hymn, became Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland (“Now come, the nation’s savior”); here Luther used music based on a melody of unknown origin, and this combination has since been used by many German composers, including Michael Praetorius and Bach.

Third, words were adapted and music borrowed from a secular source. For example, Innsbruck, ich muss dich lassen (“Innsbruck, I must leave you”) became O Welt, ich muss dich lassen (“O World, I must leave you”). Here the text adaption is by Martin Luther with music based on an original tune by Heinrich Isaac. The chorale tune has been used by many German composers, including Sebastian Knüpfer (one of Bach’s lesser-known predecessors at Leipzig) and Bach.

Collaborating Composers

As suggested, Luther often worked with others in composing and shaping hymns. His significant partnership with Walter (1496–1570) was not unlike that of Gilbert and Sullivan: lyricist first and composer second. Walter was a singer, composer, and choirmaster to the Elector of Saxony and was an influential musician. Walter founded and led the local choral society that performed for school festivities, incidental music for plays in Latin and German, and religious and civic events, and its members included one of Luther’s sons. Together they published the first collections of Lutheran choral music, which were the most popular German music publications in the middle of the 16th century: Achliederbuch (1524), Enchiridion (1524), and Geystliche Gesangk Buchleyn (1524).

Another important collaborator was Conrad Rupsch (1470–1530), a composer and reformist adviser who worked with Luther to provide chorales in a variety of styles for every Sunday of the liturgical year. In addition, there was Justus Jonas (1493–1555), a close friend of Luther’s who was a composer, reformer, and translator of many of Luther’s writings back into Latin.

Lutheran chorales were intended to be sung monophonically (in unison) by the congregation. They were also set for publication typically in four parts—soprano, alto, tenor, bass—with the melody in the tenor voice in some (more effective with trained choirs) and the soprano voice in others (more practical for congregational singing).

In any case, Luther’s passion that people understand also drove his liturgical music, so the congregation could take an active part in the service:

I would that we had plenty of German songs which the people could sing during Mass, in the place of, or as well as, the Gradual, or together with the Sanctus and Agnus Dei. But we lack German poets, or else we do not yet know of them, who could make for us devout and spiritual songs, as Paul calls them [Eph. 5:15].

In 1524, Luther produced the Deutsche Messe as an alternative to the Catholic Mass, based upon Gregorian liturgy and music, simplified with German options. Each church could design their liturgy with as much German or Latin as they wished, freely interchangeable.

This is but a brief survey of the ways Luther shaped not only Lutheran but also Protestant hymnody, not just in Germany but, in some ways, worldwide. We rightly honor Luther for his keen theological insights, but we do well to remember this other significant legacy, which reminds us that indeed, “Next to the Word of God, music deserves the highest praise.”

Colin Holman is director of orchestral activities at Loyola University Chicago and a member of the graduate faculty, School of Music, North Park University.