Deep down, I knew I had cancer before the doctor delivered her diagnosis. Still, the news came as a shock. I was 27. My wife and I had just moved to a new town, where we knew hardly a soul. We felt very much alone.

Of course, we knew and believed God’s promise to “never leave you nor forsake you” (Deut. 31:6). In church the following week, we sang the chorus “O love that will not let me go.” But this knowledge was mostly intellectual. Beneath these affirmations, we were for the first time trying to understand the meaning of God’s presence in our newly unmistakable mortality.

The question of God’s presence in mortality is central to a significant, but seldom recognized, day in the church’s yearly calendar. Holy Saturday is that odd day between Good Friday and Easter Sunday during which Jesus Christ—life himself!—lay dead in a tomb. Before my diagnosis, I had never much pondered the significance of this fact. The church has had little difficulty fixing its attention on the dying of Christ, and even less difficulty on the rising of Christ, but the being dead of Christ has found relatively little expression in its theology and liturgy. Holy Saturday, however, has an integrity of its own. If the church can attune its ear to its frequency, so easily drowned out by the dominant tones of Good Friday and Easter, it may be able to hear a profound word about human living and dying between the Cross and the Resurrection.

Christ the Superhero

Christians have found two primary ways to understand how and why Christ descended ad inferos (literally “to those below”). The predominant interpretation by the early church, what we might call the classical view, stressed Christ’s glory and power in his descent to the underworld. The fourth-century monk Rufinus of Aquileia was one of the first church fathers to write about it:

It is as if a king were to proceed to a prison, and to go in and open the doors, undo the fetters, break in pieces the chains, the bars, and the bolts, and bring forth and set at liberty the prisoners. … The king, therefore, is said indeed to have been in prison, but not under the same condition as the prisoners who were detained there. They were in prison to be punished, he to free them from punishment.

Here, Christ’s divine power, rather than his human suffering, takes center stage. Alyssa Lyra Pitstick, a Roman Catholic theologian, calls Christ’s descent “the beginning of the manifestation of his triumph over death and the first application of the fruits of redemption.”

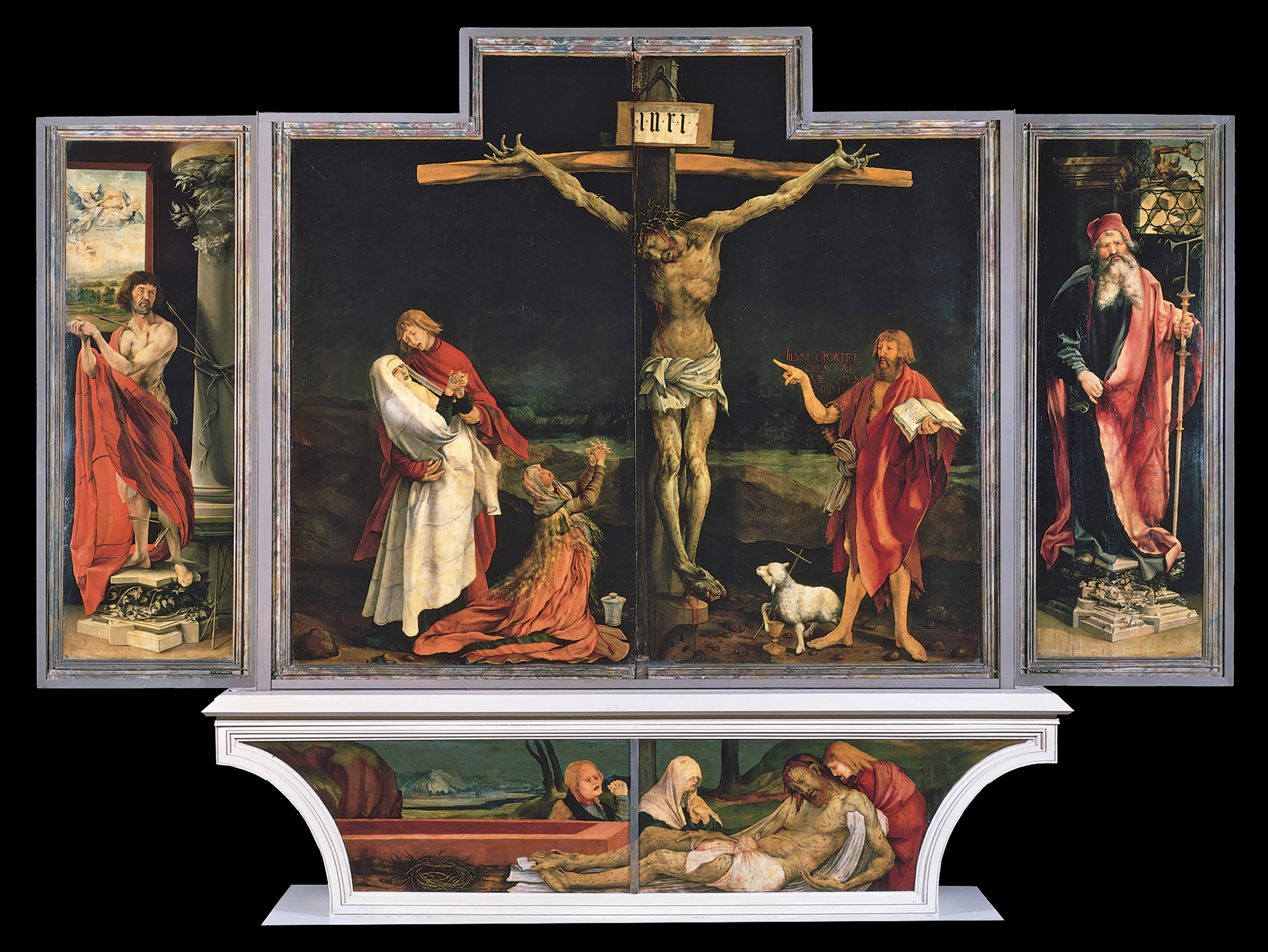

As a visual representation, consider the anastasis icon of the Maestà Altarpiece (1), from the 13th century. Less common today, works of art like this were traditionally placed behind the elements of the Eucharist on the altar. They bear collections of images that typically depict the entire life of Christ, from Gabriel’s announcement to Mary to Christ’s ascent and reign in heaven. The anastasis portion (named for the Greek word for resurrection) depicts Christ being raised from the dead.

Mondadori Portfolio / Hulton Fine Art Collection / Getty Images

Mondadori Portfolio / Hulton Fine Art Collection / Getty ImagesIn this version, painted by Italian artist Duccio di Buoninsegna, Jesus breaks the bronze doors, trampling the Devil underfoot. Think Jesus as superhero, Jesus as Schwarzenegger, Jesus as Rambo, infiltrating an enemy camp to rescue POWs. Metropolitan Hilarion Alfeyev, a bishop of the Russian Orthodox Church, wrote that “Christ descended into hell not as the devil’s victim but as Conqueror.”

The Eastern Orthodox worship service known as the Matins of Great Saturday expresses this sentiment beautifully. The gathering begins with a grave (epitaphion) erected as the focal point in the middle of the church and includes a reading of Psalm 119, a customary funereal psalm.

The typically mournful tone associated with this psalm, however, is subtly overturned through a series of exultant responses, climaxing with the singing of the Paschal troparion (“Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death, and upon those in the tombs bestowing life”), which signals the beginning of paschal joy. In fact, the dominant theme of the service is Christ’s glorious and powerful triumph over death and the Devil; the Matins of Great Saturday is clearly an anticipatory celebration of Christ’s resurrection.

But the shortcoming of the classical take on Christ’s descent, for all its theological richness and truth, is that it plays too much to our collective desire to move past suffering into glory. In its eagerness to express Easter joy, it threatens to eclipse, and therefore obscure, the theological integrity and significance of Holy Saturday.

Christ the Sufferer

During the Protestant Reformation, a different view gained prominence, and its leading proponent was John Calvin. Calvin rejected the notion that Christ saved souls from limbo (“Nothing but a story!” he scoffed). Instead, he interpreted the descent into hell as a metaphorical expression of the fathomless depths of Christ’s suffering, especially spiritual suffering, endured on the cross.

This interpretation reflected Calvin’s emphasis on Christ’s substitutionary atonement. Drawing on Gregory of Nazianzus’s ancient axiom, “What has not been assumed [by Christ], has not been healed,” Calvin boldly asserts that our spiritual healing requires that Christ suffer not just biological death but also the “agony of death” (Acts 2:24), the “terrible abyss” of feeling “forsaken and estranged from God.” For Calvin, the descent into hell is the obvious theological next step of Christ’s cry of dereliction from the cross: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” (Mark 15:34). If Christ is triumphant, according to this view, it is only through his passion.

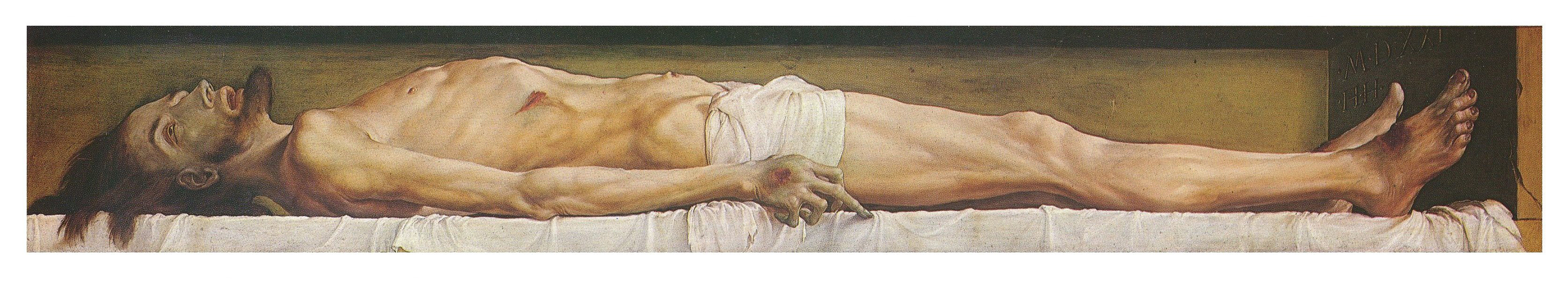

This “passionate view” finds expression in another famous 13th-century painting, the Isenheim Altarpiece (2), by German artists Nikolaus of Haguenau and Matthias Grünewald. This collection of images also depicts scenes from the life of Christ. A notable feature of this altarpiece is that it opens like a cabinet, with two sets of doors, or “wings,” that are painted with vivid imagery from the Gospels so they can be opened or closed to display different images at different times during the church year.

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsOn most days of the liturgical year, the Isenheim Altarpiece’s wings are closed, displaying the image of the crucifixion of Jesus Christ. Few graphic representations depict the extent of Christ’s physical and spiritual agony like this one. Open the wings, however, and we encounter scenes that emphasize Christ’s divinity, such as the annunciation to Mary, the Nativity, and Jesus’ resurrection. Open an additional set of wings and we see images of the church in eschatological glory, represented by gilded saints. The church’s glory is hidden in the divinity of Christ, but the divinity of Christ is hidden in his very human suffering and crucifixion.

If the Orthodox liturgy of Holy Saturday is essentially an anticipatory celebration of Easter, the absence of attention to Holy Saturday in many Protestant denominations makes it into an extended observance of Good Friday. The Presbyterian Church (USA) Book of Common Worship, for example, concludes its liturgy for Good Friday with the instructions, “All depart in silence. The service continues with the Easter Vigil, or on Easter Day.”

This practice is thoroughly in line with Calvin’s emphasis on the Cross as the center of salvation. For Calvin, as with the Book of Common Worship, the “action,” so to speak, occurs on Friday. For this reason, the Roman Catholic theologian Hans Urs von Balthasar once claimed that Calvin had more or less rendered Holy Saturday “superfluous.” Of course, a liturgical gap—a pregnant pause—could be a meaningful way to attend to the meaning of Holy Saturday. In practice, however, we tend to treat the extended silence of Good Friday as a way to simply move on.

Hearing Holy Saturday

Both of our most common approaches to Holy Saturday miss its full meaning. I would like to highlight a third line of interpretation, which stresses the fact that God in Christ takes on our mortal nature and thereby makes it his own. Because it focuses on Christ’s suffering with us, we might call it the compassionate view.

In addition to victory and suffering, this approach adds a radical reaffirmation of the totality of the Incarnation, which is not suspended in any way during the hours between cross and resurrection. God was indeed in Christ (2 Cor. 5:19) even while Christ lay dead in a tomb. This (admittedly inconceivable) thought, according to the late Reformed theologian Alan Lewis, “forces us to think at deeper levels yet, of who God is and how God works: present-in-absence, and absent where most present; alive in death, and dead when most creative and life-giving.”

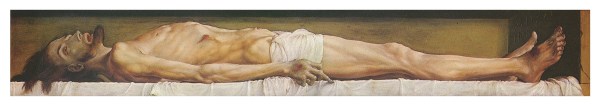

The Body of the Dead Christ in the Tomb (3), by 16th-century German painter and printmaker Hans Holbein the Younger, is a rare attempt to depict Jesus Christ in the tomb on Holy Saturday. It is also a fitting pictorial representation of this third view.

WikiMedia Commons

WikiMedia CommonsEyes toward heaven, mouth agape, Jesus’ continued relation with the Father is hinted. We have seen a similar expression on his face in images of the descent of the Holy Spirit at his baptism. But Jesus is truly dead (indicated by the rigor mortis and gangrenous coloration of his hand and face). Though the grotesque realism of the image is in line with late medieval (macabre) sensibilities, the image ultimately serves as a reminder of the miracle of resurrection and the totality of the Incarnation.

There are pastoral implications to such an interpretation of Holy Saturday. In a world living a Holy Saturday existence, in which God often seems absent, the compassionate view tells us that if God can be present in the death of Jesus Christ, then God can be and is present even where he seems most distant. During a 2010 visit to the famed Shroud of Turin, a linen cloth that is believed by some to bear the imprint of Jesus’ face, Pope Benedict XVI offered a reflection on the importance of Holy Saturday for addressing the spiritual darkness of our contemporary world:

[A]fter having passed through the last century, humanity has become especially sensitive to the mystery of Holy Saturday. God’s concealment is part of the spirituality of contemporary man, in an existential manner, almost unconscious, as an emptiness that continues to expand in the heart. . . . After the two World Wars, the concentration camps, the gulags, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, our epoch has become in ever great measure a Holy Saturday.

This is a distinctively modern interpretation of Christ’s descent, emphasizing divine solidarity with the human condition of mortality and vulnerability. The church has long taught that Jesus Christ is the definitive revelation of the nature of both God and humankind. So if God was in Christ in the grave, then death cannot be wholly alien to God, and neither can it be wholly alien to the human condition. On this basis, Alan Lewis boldly claims: “The New Testament story of the cross and empty tomb is the profound and dramatic confirmation of the Creator’s yes to our mortality.” This in no way denies the resurrection of Christ or the hope for new creation but rather affirms each as an eschatological surplus. Resurrection and new creation come as a result of God’s abundant grace from above and beyond the possibilities of our current reality. As C.S. Lewis repeatedly wrote, “Nothing in you that has not died will ever be raised from the dead.”

Is there a way for us to highlight the significance of Holy Saturday? Is it possible, in Augustine’s words, “to see darkness, to hear silence”? Perhaps, yes. In the Revised Common Lectionary, the Liturgy of the Word on Holy Saturday draws attention to the burial of Christ (John 19:38–42 or Matt. 27:57–66) while also striking a balance between acknowledging the transience of human life (Job 14:1–14) and recognizing the hope that Christ’s redemption reaches even to the lowest places (1 Pet. 4:1–8). Furthermore, the practice of observing Easter Vigil, though it technically belongs to Easter Sunday, emphasizes the tension between the already and the not yet, which marks Christian life between Cross and Resurrection. Therefore Easter Vigil is an appropriate and desirable way to nurture attention to Holy Saturday.

Church historian Eamon Duffy describes an interesting late-medieval English practice associated with Holy Week. On Maundy Thursday, three hosts (bread, which is Christ’s body in the Lord’s Supper) were consecrated. The first was used for Communion on Thursday. The second was used for Communion on Good Friday. The third was placed in a pyx, which is a special container, then wrapped in linen and placed in a stone sepulcher on the north side of the church on Good Friday. In this way, the medieval Christians literally buried the body of Christ. Believers would then keep vigil until Easter morning, when the host was returned to its usual place above the altar. Contemporary high church Anglicans have an analogous practice: After consuming all of the host on Good Friday, the door to the tabernacle, which typically stores the reserve sacrament (bread and wine from Communion that is kept for services during the week), is left open on Saturday to demonstrate the visible absence of Christ’s body. These creative liturgies, and others, have the possibility of becoming ways to express God’s solidarity with humanity, which “neither death nor life” can ultimately thwart (Rom. 8:38–39).

Of course, for many churches, liturgies are not simply formulated out of thin air but are specific, historical traditions that the church takes up and enacts. Some churches may have more freedom to improvise than others. All who repeat the creed, however, must come to terms with the meaning of Holy Saturday, when “he descended.” Whatever else it means, this phrase proclaims that God’s solidarity with the human condition extends at least six feet under the earth. Even in the grave, Jesus is still Immanuel, God with us.

As I now reflect on my experience of a cancer diagnosis and successful treatment, I can’t escape seeing my life in the light of Holy Saturday—in all its dimensions. Christ indeed was victorious over death and Hades. He also suffered the spiritual suffering that we experience. But, more than anything, he is with us through it all.

Travis Ryan Pickell is associate director of university engagement at Anselm House in St. Paul, Minnesota.