In this series

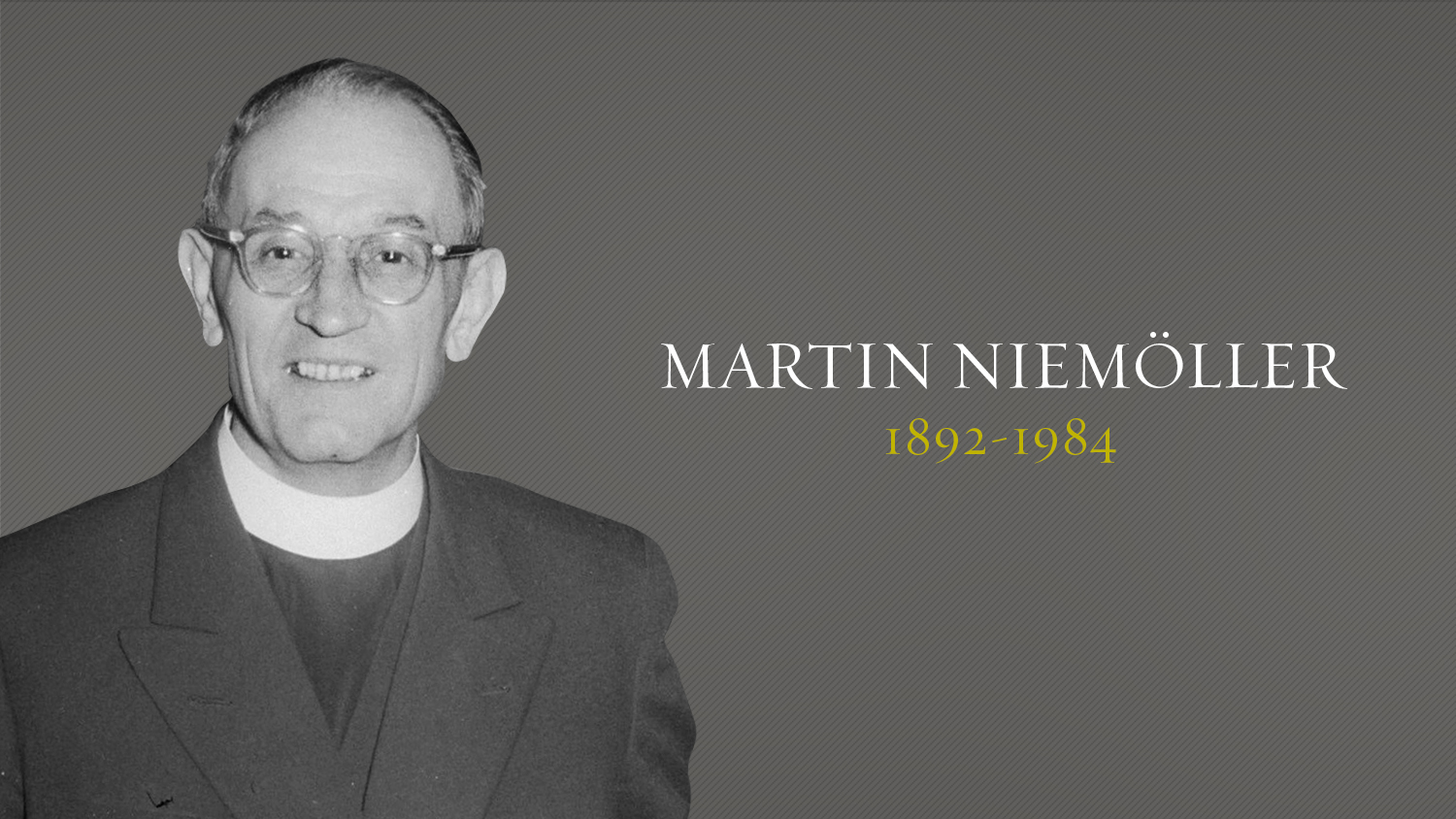

In 1930s Nazi Germany, Martin Niemöller played a crucial role in organizing the Confessing Church, an ecclesial movement that resisted Adolf Hitler’s interference in German Protestant affairs. As punishment for his protest, Niemöller was imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps from 1938 to 1945. Due to his outspoken critique of Hitler’s efforts to dominate the church, Niemöller is remembered as one of the few German Protestants who openly defied the Nazis.

Yet behind Niemöller’s protest stands a much more complex story and profound personal transformation. During elections in 1924 and 1933, Niemöller had actually voted for the Nazi Party in the hopes that a strong and powerful leader might unify the German nation and restore it to greatness following its crushing defeat in the First World War. While he protested Hitler’s meddling in the church, he was still a committed nationalist, and he remained so even as he sat in a Nazi prison cell. Having commanded U-boats in Germany’s imperial navy in the First World War, he even offered his services to the Nazi military in the Second World War.

Only in the years after 1945 did Niemöller repent of such political and nationalistic support of the Nazis. In wrestling with his past, he realized that his Christian faith had been taken captive by an ardent nationalism and a fervent militarism. While he had protested the Nazi intrusion into the church, he had failed to challenge the Nazi state outside of this spiritual realm.

Ultimately, Niemöller’s captivity as a Nazi prisoner fostered a slow yet powerful transformation within him. Following the Second World War, he left behind his nationalism for a devoted ecumenism and forsook his militarism for a principled pacifism. Having confessed his wartime guilt and repented of his complicity with the Nazis, Niemöller dedicated his remaining years to the pursuit of justice and reconciliation through the power of the gospel.

For Kaiser and Empire

Born in 1892, Niemöller grew up in an era in which Germany was quickly rising in the world as a powerful international empire. As Germany strove for imperial glory, its Protestants readily supported their emperor, Wilhelm II, in his imperial mission. As a young man, Niemöller regularly heard it proclaimed that God had providentially chosen the German nation to be a vessel of divine salvation in the world. Readily adopting such ideas, Niemöller affirmed that the German cause of “throne and altar” were one and the same.

Seeking to advance these twin causes, Niemöller became a cadet in the quickly expanding Imperial German Navy at the age of 18. Four years later in 1914, Wilhelm II’s plans for German greatness submerged Europe into chaotic conflict. As the Great War dragged on, Niemöller worked his way up to the command of a U-boat submarine that would terrorize the open seas.

Although the Great War inspired a new wave of theological reflection throughout Europe, Niemöller’s nationalism remained unshaken. In contrast, a young Swiss theologian named Karl Barth began to challenge the reigning imperialist theology. Although Barth had studied in the same nationalist environment as Niemöller, the Swiss pastor began to question his theology teachers as they declared their support for the Kaiser’s war effort. Claiming that they had idolized the German nation, Barth ultimately rejected their theology.

Such thinking, however, would not resonate with Niemöller until much later in his life. At the end of the Great War, Niemöller instead insisted that the German nation had been betrayed by socialists who had overthrown the empire and established the secular and liberal Weimar Republic.

In the chaotic postwar landscape, Niemöller counted himself among the many disillusioned conservative nationalist Protestants who openly opposed the Weimar Republic. To further advance the cause of the German nation and the church, he made his way from command of a U-boat to a preacher’s pulpit.

As the new pastor watched Weimar Germany suffer from economic and political instability, he began to long for a strong political leader who would promote national unity and restore German honor. In 1924 and 1933, Niemöller cast his vote for the Nazis, believing that Hitler might fulfill exactly those aims. As Hitler campaigned for office, he emphasized the importance of Christianity in Germany’s renewal, a commitment which greatly appealed to Niemöller.

Leader of the Confessing Church

Shortly after Hitler’s electoral victory in 1933, Niemöller watched on without protest as Hitler established a dictatorship. His warm welcome of Hitler only cooled once the Nazi leader began to interfere in the affairs of the Protestant church. A stalwart believer in Luther’s two kingdoms doctrine, Niemöller claimed that the church and the state should both advance Germany’s cause while not interfering in each other’s respective mission of proclaiming the gospel and creating temporal order.

Hitler violated such a dualistic principle, however, as he intervened in Protestant church elections and campaigned for the “German Christians.” A resolutely pro-Nazi group, the “German Christians” desired to completely “Aryanize” the German Protestant church. Their platform called for purging Christianity of all Judaic elements, including removing the Old Testament from the Bible and recasting Jesus as a blond-haired, blue-eyed Aryan.

While he had a low religious respect for the Jews as a people, Niemöller condemned such teachings as heresy. When the Nazi government announced the Aryan Paragraph, a law which forbade Jews from holding public office, the German Christians called for banning Jewish converts from the pastorate as well. As the German Christians made race the crucial component of Christian identity, Niemöller organized the Pastor’s Emergency League, which rallied together roughly 6,000 pastors to oppose Nazi interference in the church’s life.

By 1934, the League had organized a broader ecclesial movement known as the Confessing Church that further challenged the German Christians. Niemöller and Barth joined forces with other League pastors in authoring the Barmen Declaration, a theological treatise that denounced Aryan ideology and proclaimed that Scripture and the Reformation confessions alone could determine church practice and teaching.

Yet despite Niemöller’s pushback against Nazi interference in the church, he remained a fervent nationalist and defender of the Nazi’s foreign policy. On this point, Niemöller differed radically from Barth and another Confessing Church leader, Dietrich Bonhoeffer, who called on the Confessing Church to openly challenge Nazism outside of the church as well. However, their pleas went unheeded. Along with Niemöller, the Confessing Church as a whole granted Hitler free reign in the rest of German society.

As Hitler sought to synchronize all aspects of German life under his dictatorial rule, Niemöller’s leadership in the Confessing Church was a thorn in his side. With the Confessing Church proving difficult to completely silence, the Nazis began intimidating Niemöller through arrests, interrogations, and preaching bans. Hitler then moved to stifle all dissent in 1937, formally arresting Niemöller for treason and imprisoning him for seven months while awaiting trial.

When the court system acquitted Niemöller of treason, an enraged Hitler ordered his secret police to seize and imprison him in the Sachsenhausen and Dachau concentration camps. From 1938 to 1945, Niemöller remained Hitler’s personal prisoner alongside other enemies of the Nazi state. As he sat in solitary confinement, Niemöller reported that he nourished his spirit through reading his treasured Bible and ministering to his fellow prisoners. Nonetheless, Niemöller’s love of the German nation and militaristic spirit endured. When Germany began World War II, he petitioned to be released in order to serve in the German navy.

Postwar Transformation

After being liberated by the Allies in 1945, Niemöller began to experience his own road to Damascus moment when he returned to Dachau as a free man. He reflected that God began to challenge him to account for the years of 1933 to 1945. In response, he could muster no alibi. As Niemöller wrestled with his limited course of action in those years, he wrote the following poem:

First they came for the Communists, and I did not speak out, because I was not a Communist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out, because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out, because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

Niemöller came to the painful realization that his love of nation had overpowered his love of God and neighbor. While he had defended the German church and nation, he had overlooked and failed to defend “the least of these.” He confessed his lack of solidarity with the Jews and other Nazi enemies—those he had deemed anti-Christian and anti-German—had only furthered Hitler’s ruthless dictatorship.

Such painful realizations proved fertile soil for new growth. Niemöller now resolved to speak out for all those oppressed and persecuted in the world, regardless of their race, religion, or politics. As Germany emerged from the rubble and ruin of total war, such a commitment made Niemöller a crucial postwar church leader. Seeking to lead the church in repentance and renewal, he authored the Stuttgart Declaration of Guilt, which confessed Germany’s collective guilt in not opposing Hitler and the Nazi war effort. He then embarked upon a trip of reconciliation to the United States, modeling in the process the transnational ecumenism that he hoped would defeat German nationalism.

When the threat of military conflict rose in the Cold War, he practiced a radical discipleship as one of the most outspoken supporters of Christian pacifism. Forsaking his devotion to nationalism and militarism, Niemöller beat swords into plowshares as he committed his life to the pursuit of justice and reconciliation in Christ. As such, Niemöller’s heroism ultimately lay not so much in his courageous but limited stand against Hitler as in his genuine willingness to repent and make amends.

James Strasburg is an assistant professor of history at Hillsdale College. His forthcoming book, God's Marshall Plan: The American Mission to Save the Christian West , examines the American Protestant effort to revive European religious life in the 20th century.