Fans have prayed for years for Big Daddy Weave bassist Jay Weaver as he endured chronic health conditions and multiple hospitalizations.

This week, his brother and the band’s frontman Mike Weaver announced that “those prayers for healing can turn into prayers for thanksgiving now that Jay is in God’s presence.” Jay died Sunday after contracting COVID-19. He was 42.

“The Lord used him in such a mighty way on the road for so many years,” Mike Weaver said in a video clip. “Anyone who came in contact with him knows how real his faith in Jesus was. I believe that even though COVID may have taken his last breath, Jesus was right there to catch him.”

Big Daddy Weave topped Christian charts and earned spots as K-LOVE fan favorites with songs like “Every Time I Breathe” and “Redeemed.”

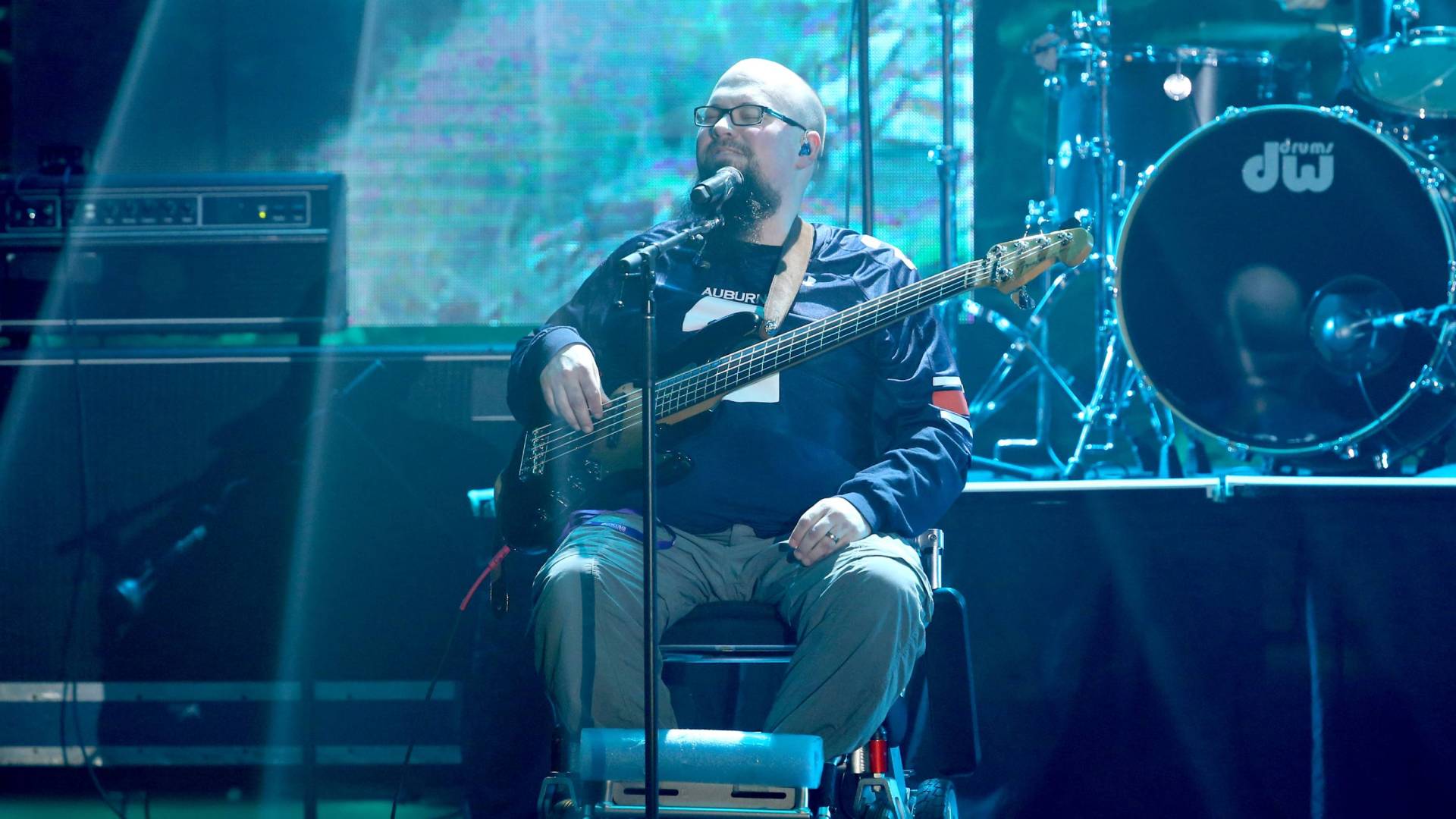

The band’s 2019 album, When the Light Comes, emerged out of Jay Weaver’s health struggles. He had diabetes and a weakened immune system, which led to the amputation of both feet due to infection in 2016.

Over the years, Jay Weaver shared his testimony of near-death experiences as his conditions worsened as well as the self-doubt he had to face after his legs had been amputated.

“It’s a fairly lonely bed to lay in—until the Lord is remembered,” he said in a 2017 interview. “I’m lying in this hospital bed by myself, but the Lord is the best I know of anybody to come down and get in our junk with us, and that’s exactly what he did.”

Fans lifted Weaver up in prayer and read updates through the band’s social media as he underwent surgeries and treatment. At shows and events, where Weaver appeared in a wheelchair or in prosthetics, he said people often came up to say they had prayed for him.

Weaver had to pause from touring with the band to due to his health; he spent time in intensive care over the summer and had been hospitalized in December with COVID-19.

His favorite part of going on tour was seeing the band’s music minister to people. “It gives us something to look forward to … the expectation of God doing something in the hearts of people and physically seeing it with our own eyes,” Weaver said.

Chris Tomlin, who toured with Big Daddy Weave, called Weaver “a great light and a true heart for Jesus.” Steven Curtis Chapman wrote that his “smile, kindness, generosity and life reflected the light of Jesus in a beautiful way! So thankful that I got to know him this side of Heaven.”

Big Daddy Weave formed in 1998 at the University of Mobile in Alabama. Two years ago, the band was featured in a TBN reality series, where they discussed their spiritual journeys, the demands of touring, and the emotional heaviness around Jay Weaver’s amputation and health struggles.

“Praise God that he is the God of a million and one chances,” he remarked. “All I can say is today, I’ll put my best fake foot forward.”

Weaver leaves behind his wife, Emily, and three children.

When Mike Weaver broke the news of Jay’s death on Sunday he said he was sorry to share it but also “excited to celebrate where he is right now.”

In “The Only Name (Yours Will Be),” Big Daddy Weave sings:

When I wake up in the Land of Glory With the saints I will tell my story There will be one name that I proclaim Yours will be The only name that matters to me The only one whose favor I seek The only name that matters to me