In this series

“The Resurrection has proved its power; there are Christians—even in Rome.” This is how Karl Barth, renowned Swiss theologian, described the conversion of the Roman Christians in his famous work The Epistle to the Romans. What he meant was that the resurrection of Jesus Christ had proved its reality because there were, in fact, Christians in Rome, the capital of the oppressive empire whose authority had crucified Jesus, and that was indeed sufficient grounds for thanksgiving and belief.

As I reflected on the words of Barth, I couldn’t help but realize that as he was describing the faith of the Roman Christians, he was also telling the story of black Christianity. The simple fact that the enslaved were able to “hold on” to Jesus, as it were, is in our day a story of the power of the Resurrection. Emerson Powery and Rodney Sadler Jr. shared in their book, The Genesis of Liberation, “African-Americans’ respect for the authority of the Christian Scriptures is a miracle in itself.”

You have to look no further than to the “Christ” they were introduced to to see the miracle. The “Jesus” they met in the Middle Passage and on the plantations was firmly on the side of the oppressor and opposing their freedom. This experience was not a neutral one. He clearly was used by the slavers and planters to pacify the slaves and to justify their enslavement. He clearly anointed and appointed the oppressors, not for the ministry of reconciliation but for their “ministry of subjugation.” He was the “White Man’s Jesus.”

In spite of this introduction, Powery and Sadler conclude that many African Americans, though not all, became Christians and attributed authority to the Bible. The question that remains is why. Why did enslaved Africans embrace the religion of their captors, who used the Bible to justify the brutal trans-Atlantic slave trade?

Powery and Sadler’s simple answer is that “they fell in love with the God of Scripture.…In Christ they found salvation from their sins and reconciliation.” They conclude that though this was certainly enough, there was more to the answer. They write: In these texts they found not just an otherworldly God offering spiritual blessings, but a here-and-now God who cared principally for the oppressed, acting historically and eschatologically to deliver the down trodden from their abusers. They also found Jesus, a suffering Savior whose life and struggles paralleled their own struggles.

In the biblical narratives that described these characters the enslaved Africans found reasons to believe not only in the liberating power of the God of Scripture, but in the liberating emphasis of Scripture itself. Because they learned that the Bible did not denigrate African identity, they were able to use it to ground their humanity, subversively to rebut biblically based supremacist readings, to validate their right to be free and function as equals in this nation.

As they came in contact with this God, they found a different reality in him: the reality of Resurrection power. It was this reality that provided the basis for what would be deemed by historians Sylvia Frey and Betty Wood as “perhaps the defining moment in African American history” because “it created a community of faith and … provided Afro-Atlantic people with an ideology of resistance.” The Resurrection had proved its power; there are Christians—even among African Americans.

The Black Reformation of 1736

If the Protestant Reformation of 1517 is deemed the greatest religious movement in European history, then one could conclude that the Black Reformation of 1736 is the greatest religious movement in American history. But this begs the question, can it be called a “reformation”? Author Juan Williams argues indeed it can be. In his book on African American religious history, This Far By Faith, Williams writes, “Africans did not simply adopt the religion of the European Colonist; they used the power, principles, and practices of Christianity to blaze a path to freedom and deliverance.” Not only did they blaze a path but the path was so big that he concludes that “it reformed Christian theology” as well as Christianity itself.

Rebecca Protten, ‘Mother of the Black Reformation’

Though the process had long begun, in the 1730s, the birth of one of the earliest African Protestant churches found pivotal momentum in a seemingly unlikely place: the rugged roads through the hills of St. Thomas, a Danish sugar colony in the West Indies, known to the enslaved as “The Path.” Though kept from popular nightly meetings due to violent animosity, black men and women would press their way along these rugged roads to hear the gospel from an unlikely missionary: a brave young woman. She would not be just the “Mother of Modern Missions” but also the “Mother of the Black Reformation.” Her name was Rebecca Protten.

Born a slave in 1718 and kidnapped at an early age from the island of Antigua, she was converted as a young woman. Protten would eventually gain her freedom and join a group of German missionaries from the Moravian Church in 1736. Freidrich Martin, a Moravian missionary, wrote that Protten had done “the work of the Savior by teaching … and speaking.” Protten didn’t just give her voice to the mission of God; she gave her life. Jon Sensbach notes in his book Rebecca’s Revival that she would trudge “daily along rugged roads through the hills in the sultry evenings after the slaves had returned from the fields.”

She was more than a teacher; she was a mentor. She was “a prophet, determined to take what she regarded as the Bible’s liberating grace to people of African descent.” She took her message near and far by carrying it directly to the people. Her travels “took her to the slave quarters deep in the island’s plantation heartland, where she proclaimed salvation to the domestic servants, cane boilers, weavers, and cotton pickers whose bodies and spirits were strip-mined every day by slavery.”

As she and others took the gospel from plantation to plantation “St. Thomas suddenly became the Americas’ new axis of Afro-Protestant conversion.” Fueled by the message of liberating grace, they put “themselves at the forefront of an indigenous black movement that was birthed in the slave quarters.”

Sensbach concludes, “much that we associate with the black church in subsequent centuries—the anchor of community life, advocate for social justice, midwife to spirituals and gospel music—in some measure derives … from those early origins.” This Reformation spirit found its home in two women and two men.

Freedom’s Prophet: Richard Allen and The Black Reformation

“If I could write but a part of my labors, it would fill a volume.”

These were the words of Bishop Richard Allen in his spiritual autobiography Life, Experiences, and Gospel Labors.

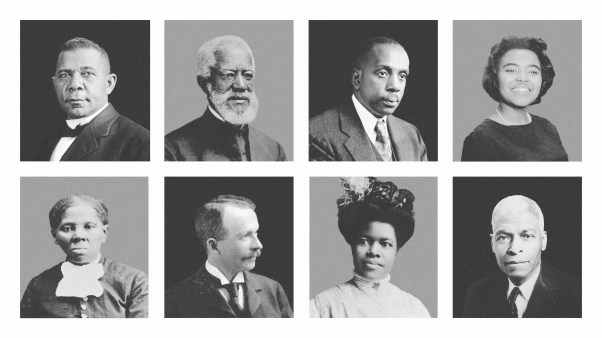

Born into slavery in 1760, Richard Allen went on to become a leading American reformer, wrote many pamphlets of protest that would be the model for many generations to come. A pastor who was a contemporary of Allen’s called him one of the most “talented people of his generation.” Another dubbed him “The Apostle of Freedom.” Allen’s other contemporaries agreed. His life would be celebrated and would inspire the likes of the pioneering abolitionist Frederick Douglass, famed abolitionist David Walker, and great sociologist W. E. B. Du Bois.

At the age of 17, Allen “got religion” and converted to Methodism. His passion was undeniable. He would begin and end each day with prayer. Allen believed he had an important place in God’s mission. As one biographer shares, “The Lord looked for young Richard Allen, a slave, and Allen professed to be the Lord’s undying servant.” Allen joined St. George’s Methodist Church in Philadelphia and preach at the 5 a.m. special service for African Americans, attracting many new black parishioners.

Unfortunately, in 1787, racial tensions got the best of the congregation of St. George’s. One morning while attending the church, segregated seating was instituted. Allen, not one to lack courage, believed this was a sign that a separate church was necessary for black congregants. Allen and the black congregants walked out and formed what would become Bethel A.M.E. Church. This ministry would not just struggle for the advance of the gospel; it would also struggle for racial justice in America, be home for the benevolence of African American peoples and would be a church that would support missions in several countries overseas. Allen died in his home in 1831, but his legacy changed the world. If Rebecca Protten is the “Mother of the Black Reformation,” then surely Bishop Richard Allen is its father.

In the spirit of Mary: Jarena Lee and the Black Reformation

As we look back on black church history, much time has been devoted to the black men who utilized their lives to create indigenous movements throughout America. Less attention has been given to the crucial role that black women, specifically the itinerant female preachers of the A.M.E. and other black denominations, had in helping to shape what we know as black Christianity today. As the Resurrection power caught fire in St. Thomas through Protten, a similar figure arose in the United States—Jarena Lee.

Born in a poor but free family in 1783, Jarena Lee moved to Philadelphia as a teenager to continue her life as a domestic servant. After hearing the sermon at a worship service at Bethel Church, founded by Allen, she was so moved that she converted to Christianity. Shortly after, Lee came to believe that she was commissioned by God to preach the gospel. This did not go over well in the male-dominated nature of the church.

Paul Harvey shares in Through the Storm, Through the Night, that “male leadership respected the women’s spiritual power and call to exhort, but they refused to recognize their call to ministry.” Yet that did not stop women from pursuing that call. Harvey shares that these women “responded to profound stirrings, attracting sizable audiences through the nineteenth century.” Jarena Lee is a prime example. She defended her ministry by asking: “Did not Mary first preach the risen Savior?” In the spirit of Mary, Lee pressed on.

As providence would have it, in 1819, a guest preacher began to struggle with his sermon and abruptly stopped preaching. As he was staring at the congregation, undoubtedly shocked by his loss of words, Lee arose and began preaching where the minister had left off.

Lee later concluded that “during the exhortation, God made manifest his power in a manner sufficient to show the world that I was called to labor according to my ability.” In the audience that day was Bishop Richard Allen himself. Earlier he hadn’t felt comfortable allowing women to speak from the pulpit, but that day he changed his mind. Historian Eric Michael Washington concludes that Jarena Lee “is not only a leading figure for African Americans during the Second Great Awakening, she is also a trailblazer for women in ministry.”

The Black Reformation Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow

With these powerful testimonials, one can indeed see the Resurrection had proved its power; there are Christians—even among African Americans.

These black Christians of old did not simply just adopt the religion of their oppressors; they used the power and practices of Christianity to blaze “The Path” of freedom and deliverance for many who would follow after. This reality didn’t just inform their thinking; it informed their living. Their theology invaded every aspect of African American identity.

When Protten traveled the rough roads of the island of Antigua, her life would be the catalyst for the life of Sojourner Truth, the slave woman turned evangelist champion for the end of slavery. When Allen decided to walk out of the dark clouds of segregation and into the sunshine of racial justice, his life would be a catalyst for the young Martin Luther King Jr. who would do the same. When Lee had the courage to stand up and proclaim God’s truth despite being a woman, her life would be a catalyst for the civil rights activist Fannie Lou Hamer, who would always say, “You have to step out and trust God.” They gave birth to what we know as black Christianity today.

This strong tradition gave a people hope that God would act to provide justice for enslaved Africans and all who were oppressed. It was this faith that gave African Americans the arguments against the religion of the slaveholders. It gave a people a profound sense of dignity, identity, and significance, which led the church to be the most enduring and shaping institution in the African American story.

Author Juan Williams writes that “individual black people took on a cloak of faith, an unshakable belief that God would carry them through slavery and lift them up to freedom.” They transformed themselves into “Christian soldiers, marching for an end to segregation and for the promise of equality as God’s children … then they transformed the church.” Much more, they transformed Christianity as we know it. It would do us well to not only listen to these stories of the past and be transformed by them in the present. May God make it so.

Dante Stewart is a student at Reformed Theological Seminary. He is a graduate of Clemson University, where he was a student athlete and received a BA in sociology. He and his wife, Jasamine, live in Augusta, Georgia, where he teaches Bible at Heritage Academy Augusta.