Megachurches have gotten so big over the years that they’ve outgrown their sanctuaries.

The average megachurch in the United States had 4,100 regular attendees (before the pandemic) and seating for 1,200. That’s because, unlike in earlier days, most now spread services across multiple sites and locations over a weekend, according to a new report by the Hartford Institute for Religion Research and the Evangelical Council for Financial Accountability (ECFA).

“The 20-year trend to become multisite … has continued to explode,” the researchers wrote in the report, a 2020 survey of 582 megachurches, defined as Protestant churches with regular attendance of 2,000 or more.

Multisite megachurches tripled between 2000 and 2020, now with 70 percent of megachurches operating as multisite and another 10 percent considering it.

Pastor Phil Hopper leads a multisite church called Abundant Life in Lee’s Summit, Missouri, a suburb-turned-city outside Kansas City. The multisite trend may be new, but to him it’s actually a return to an ancient strategy.

“We have to get back to that early paradigm of church ministry,” the pastor said. “The ‘win’ has to be ‘Wow, we just sent 500 people from here somewhere else to launch something brand new.’ … That’s what made early Christianity a move of God that swept through the ancient world.”

As megachurches continue to grow, logistically they have to add services or locations to accommodate new attendees. “You can’t keep building a bigger building every time you run out of seats,” said Hopper, whose congregation drew 7,000 attendees across two locations before the pandemic.

The average US megachurch, according to the Hartford study, has 7.6 services a weekend, compared to 5.5 just five years ago.

“Multiplying” to launch a new location, Hopper said, is sort of a shot at immortality for churches—at least logistically speaking. The Sunday that Abundant Life sent 500 people to plant their second location in Blue Springs, another Kansas City suburb, those congregants’ seats were still taken at the main campus—just by new people.

“Each organization goes through seven life cycles, from startup to eventually decline and death,” Hopper said. “Churches are no different. … Multisite is a way to interrupt that process.”

Abundant Life is planning to launch a third site in 2022, having purchased a new building for the location prior to the COVID pandemic.

Hartford Institute researchers conducted their 2020 survey before the US coronavirus shutdowns began in March. They acknowledged the effects on church life of the virus and lockdowns won’t be fully understood for some time. But the country’s largest churches are generally in a better financial position than smaller congregations to weather the crisis.

In fact, one trend that contributes to the “multisite boom”—megachurches adopting and merging with smaller, struggling churches—may well increase due to the pandemic.

“One pattern is already clear: larger churches are providing much of the thought leadership for how to spiritually navigate the crisis,” researchers wrote.

Multistrategy

Abundant Life’s satellite church in Blue Springs streams Pastor Hopper’s sermon every week. That second location has its own staff, including a campus pastor.

“If you have multiple locations but each location is hearing a different message from a different messenger, you really don’t have one church in multiple locations,” Hopper said. "You have multiple churches all with the same name.”

Not everyone agrees. Scott Thumma, who directs the Hartford Institute and co-authored the report with ECFA’s Warren Bird, said this year’s survey didn’t ask how multisite megachurches specifically approach preaching.

“There are many models for how it’s done,” Thumma said, including one sermon being simulcast into multiple locations, a senior pastor driving to different locations for multiple services, or satellite churches having their own teaching pastors. “As long as all the locations are seen by the church as a single church, then they are a multisite megachurch for our purposes.”

Pastor Brad Bell leads The Well Community Church in Fresno, California. The Well first branched into multiple sites in 2007, but Bell says not all the sites they launched are still up and running. He said simulcasting sermons from a pastor across the city into a different church was part of the problem.

“We launched a couple of campuses regionally with shepherd leaders, thinking, ‘He doesn’t have to be a leader; he doesn’t have to teach,’” Bell said. “But the magnetism of a video-teaching multisite campus is not a draw without a strong visionary leader.”

The three sites under The Well’s umbrella—meaning they share things like doctrinal statements, logos and graphics, kids’ ministry curricula, etc.—each have their own teaching pastor. They total around 5,700 weekly attendees.

Though Abundant Life does it differently, Pastor Hopper acknowledges that the same logistics that prompt churches to multiply—too many bodies for not enough seats—can create ministry difficulties. “Most human beings don ’t want to be just a face in the crowd forever,” he said. “We don ’t want to be so large that we can ’t shepherd people. … In the end, we can ’t shepherd people if they ’re not in a [small] group.”

That’s something his church and The Well have in common: Both pastors said as they grow and multiply, dividing into small groups has become a more critical part of their ministries. And most fellow megachurch pastors would agree.

Small Groups, Not Dinner Parties

In 2020, 90 percent of megachurches consider small groups as “central to their strategy of Christian nurture and spiritual formation,” compared to 50 percent 20 years ago.

The study also found that small-group attendance within megachurches is on the rise and that a larger participation in small groups correlates to other positive trends such as the growth of the church overall, the church’s involvement in community service projects, and church members’ confidence in their ability to “incorporate newcomers into the congregation.”

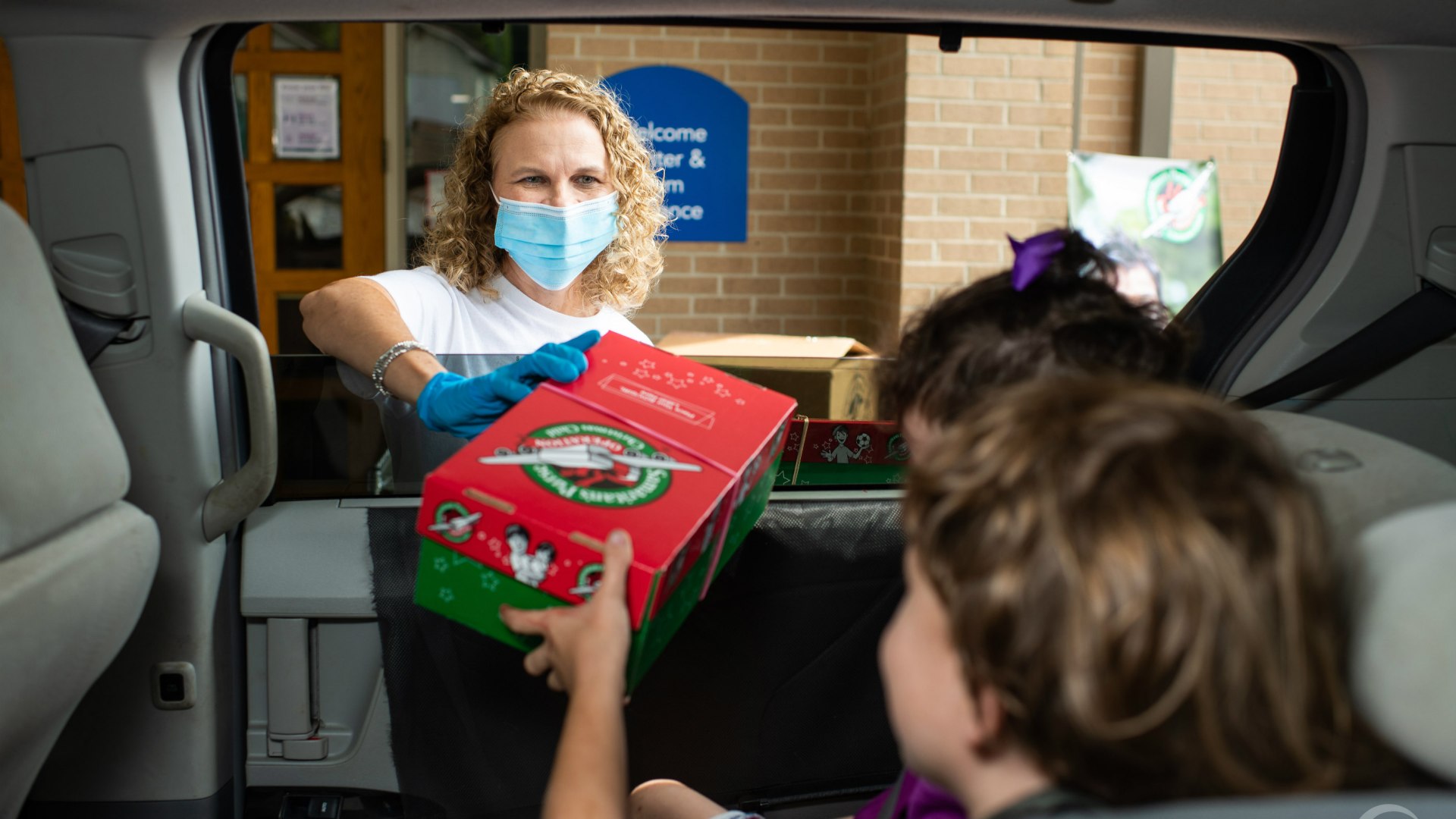

Courtesy of The Well Community Church

Courtesy of The Well Community Church“Spiritual formation doesn’t happen in the auditorium; it happens in the living room,” said Brad Bell, who is focusing his doctoral dissertation on building small groups.

Bell said he wants The Well’s small groups to focus not just on having a “dinner-six”—a three-couple dinner party that doesn’t do much else—but on practicing spiritual disciplines together.

“We have more higher-educated Christians in our churches who are living lives that do not reflect what they know,” he said. “What does it look like for a Life Group (The Well’s name for a small group) to practice simplicity or fasting? Or silence and solitude and prayer?”

Bell said every small group leader will be specifically trained and ultimately evaluated not just on building honest friendships but on pursuing spiritual formation.

Hopper said Abundant Life starts encouraging people to join small groups the moment they walk through the door. “We say … you don’t have to choose between a large church and a small church,” Hopper said. “We’re telling people that [the small group] is where small church happens.”

If small groups had become mission critical for megachurches before the pandemic, they’re especially important now, with few packing large auditoriums for worship. Hopper said small groups may be singularly responsible for keeping some of Abundant Life’s members active in church during the two months they did not meet in person.

At The Well in Fresno, Bell started streaming sermons on Instagram Live during the eight months the church was shut down. He was surprised to find that a couple in their early 90s were among those consistently tuning in each week to watch.

If they’ve been believers for a while, they’ve probably lived through several life cycles and trends of the American evangelical church but are still game for what their megachurch is doing in 2020. “They are faithfully logging on and commenting,” Bell said. “How awesome is that?”